courtesy of Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine, July 1989

The capital city of the ancient land of Israel is situated 2,500 feet above sea level, high along a strategic ridge of hills. In the ten centuries B.C., Jerusalem would become a buffer state between the warring factions of Assyria and Egypt, and later would be influenced by the Macedonian culture of Alexander the Great. By 173 B.C., Jerusalem would look like a Greek city, complete with gymnasiums. When the Romans took over, they erected elaborate buildings and water systems to accommodate them. In 73 A.D., they destroyed it all, and Jerusalem lay in ruins.

From the city’s inception, its lifeline of water depended solely on hidden wells and underground cisterns. Fed by underground streams, the Gihon Spring on Jerusalem’s eastern slope was the ancient city’s only source of water at that end. Depending on die season, die spring could supply water to the city once or of time. The Gihon also irrigated the surrounding fields and gardens through several open canals along what is known as the Kidron riverbed.

From the city’s earliest settlements even prior to 1200 B.C. water tunnels from the city tapped into the connection located just outside the city walls. As in other cultures, access to the water supply had to be insured against enemy invaders who conceivably could cut off the supply above ground.

About the late 8th Century B.C., King Hezekiel of Judah authorized the excavation of a new tunnel even further away to access water to the city, store the supply in an underground pool, and hide the entrance of the spring. In his attempt to thwart a possible Assyrian siege of the city, the tunnel would become one of the earliest examples of daring engineering feats.

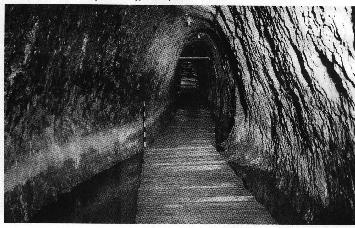

It would take two teams of workers six to seven months to literally inch their way through 765 feet of solid rock. Each team chipped the way to the center from opposite sides of the hill, extending an aqueduct south of Bethlehem to Jerusalem. Evidently guided only by water fissure, they laboriously dug out a tunnel about one yard in width, and one to three yards in height. One man would methodically and tediously hack and chip away, the others behind him passing the broken stones out in baskets. Chiseled in the rock at the point where the two teams met, archaeologists have found a Hebrew inscription recounting “the day of the tunnel” in which “the stone cutters made their way towards one another ax-blow by ax-blow.” The tunnel diverted the exposed spring of Gihon to a concealed point outside Jerusalem’s western wall.

For centuries Jerusalem was sparsely inhabited. It began to grow under the Biblical King David who made the city his capital. By the time his son Solomon was anointed king in 956 B.C., Jerusalem had become a city of crowded, narrow streets, with spacious quarters for the royal palaces and related court retinue.

The royal garrisons of King Solomon, however, were quartered on the site of Megiddo (located some 22 miles southeast of present-day Haifa), on the plain of Armageddon. Megiddo even then was an ancient fortress town, dating back at least to the lath Century B.C. The royal stables reportedly were outfitted with feeding troughs for the 492 horses of the king’s warrior corps.

The early inhabitants initially tried to sink a well shaft within the city walls, straight down to the water’s source, but couldn’t. This was still the Bronze Age and their primitive tools were no match for the hardness of the rock. Instead, they had to dig vertically and horizontally, first eking out a dark, angular tunnel. The tunnel descended by a treacherous flight of stone steps hewn from the rock; in essence a spiral staircase around a 43-foot shaft, down and around to a huge natural cave outside the wa1ls of the city. At the far end of the 75 ft. long x 25 ft. high x 15 ft. wide cave, the diggers finally tapped the spring whose water still bubbles to this day.

Sanitary laws: The ancient Hebrews were among the earliest peoples to incorporate cleanliness and hygiene into their religious observance and everyday life. Some attribute Moses’ upbringing in an Egyptian royal household for his emphasis oil the purifying aspects of water. Washing, bathing and cleanliness played a prominent role in the religious rites of the Jews, and indirectly afforded the people a greater measure of health than enjoyed by most ancient societies.

The earliest recorded sanitary laws concerning disposal of human waste also are attributed to Moses and his teachings in the Old Testament. Circa 1500 B.C., his people were instructed to dispose of their waste away from the camp, and to use a spade to turn the remains under the earth or sand. Of course, in crowded cities, more ingenuity is required.

Jerusalem’s water supply and drainage developed in stages from the ancient days, even prior to the reign of King David in 1055 B.C. Drains were built for removing sewage from homes and streets, while excess waste and refuse were carted out through the appropriately-named “Dung Gate” of the city.

Because the temples required their own “pure water” arrangements, there were two separate drain and waste water systems in the city. This was certainly an extra expense, but the early plumbers developed a conservation system for its reuse. Sink water was channeled into ponds or large cesspools or directed into a settling basin. Here the waste materials would be held in suspension and subsequently used as manure for the fields and crop lands. Any surplus water was eventually used in the cultivation of gardens.

More elaborate sewer systems were found in smaller towns of the region. They consisted of a trunk line and auxiliary drains underneath the houses.

In the courtyard of Solomon’s Temple stood what the Old Testament calls a “molten sea,” said to have held 2,000 baths. It was used by the celebrants to wash their hands and feet before entering the sanctuary. According to one source, the “sea” or laver was a replica of the apse, the layer that Babylonian priests used in their temple rites, except the Babylonian layer was chiseled out of stone.

This “molten sea” was a seven-foot high basin of bronze or brass, 15 feet in diameter and 3 inches thick. It rested on the backs of 12 cast-iron oxen which stood in four groups of three. Biblical scholars calculate the weight of the “sea” alone at 33 tons, an astounding figure which can never really be proven. The layer was situated close to the temple’s “Water Gate” with a convenient water conduit on the outside of the complex.

When 300 years later the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar ordered Jerusalem burned and its people deported to Babylonia, the temple was destroyed. Its treasures, including the lavers, were melted down or carted away as tribute.

Herodian Era: In 38 B.C., Solomon’s Temple was rebuilt again, this time by Herod, Rome’s proclaimed king of Judea. He kept faithful to the original plans, including ritual baths and layers and an extended courtyard.

Herod left his mark on other areas of the land, more notably on Masada, a 1,300 foot high butte overlooking the peat Sea. It is here that archaeologists have uncovered and partially restored his living quarters and administrative palaces. Herod incorporated the latest of Roman plumbing know-how in his citadel-for Masada is an isolated fortress of rock sitting in the middle of a desert.

Bringing water to the barren area was a stunning feat by Herod and his engineers. The water system originated in two small wadis or gullies located some distance away. Typical in a desert, the wadis quickly flooded with water from sudden, unpredictable down bursts. To hold the waters until ready for release, the Romans constructed dams in two places. On demand, they allowed the water to flow by gravity through an aqueduct and channels directed to the site.

Herod built another set of cisterns at the top of the citadel and connected them to conduits to catch rain. But the water supply was a pittance for his two big palaces and five smaller ones on the rock. Since a ruler such as Herod would not be denied the same comforts he enjoyed in Jerusalem and his other palaces around the land, he ordered a human conduit to bring up water from the cisterns far below. Some estimate a work force of hundreds, maybe thousands, of slaves and beasts of burden bearing jars of water for the royal pleasures. Heron designed Masada’s northern palace in three tiers. In Roman fashion, it featured a bathhouse with four rooms: a hot room (caldanium), cold room (frigidarium) and its small cold water pool, a larger tepid room (tepidarium) and the entrance (apotyterium) which included dressing rooms. The walls were decorated with frescoes simulating marble or alabaster walls. The entrance floors were mosaic, later to be replaced with triangular tiles. A smaller villa featured a swimming pool too.

The caldarium was the largest room, containing below a steam room whose floor rested upon 200 tiny columns of brick. Perforated clay pipe within the walls carried the forced hot air generated by an adjacent furnace. The design reportedly resembles the Roman bathhouses found at Pompeii and Herculaneum.

After Herod died, Masada was all but deserted and in disrepair. In 70 A.D. the fortress became a refuge again, this time for a band of Jewish Zealots fleeing the Roman soldiers. Girding themselves for a long siege, they settled on the opposite side of Herod’s rundown villas. In addition to carving out living quarters and storehouses, they built three pools for the ritual baths. In accordance with Jewish precepts, the mikveh allowed only rainwater and used no metal piping in the construction.

The Roman siege lasted almost three years, the Zealots’ water supply still provided by Herod’s cisterns. In 73 A.D. the 960 defenders committed suicide rather than submit to the final assault of almost 15,000 Roman soldiers.

#

good and interesting

#

what a wonderful kingdom

#

amazingly wonderful on this site.