courtesy of Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine, July 1988

The first epidemic of a waterborne disease probably was caused by an infected caveman relieving himself in waters upstream of his neighbors.

Perhaps the entire clan was decimated, or maybe the panicky survivors packed up their gourds and fled from the “evil spirits” inhabiting their camp to some other place.

As long as people lived in small groups, isolated from each other, such incidents were sporadic. But as civilization progressed, people began clustering into cities. They shared communal water, handled unwashed food, stepped in excrement from casual discharge or spread as manure, used urine for dyes, bleaches, and even as an antiseptic.

As cities became crowded, they also became the nesting places of waterborne, insect borne, and skin -to-skin infectious diseases that spurted out unchecked and seemingly at will. Typhus was most common, reported Thomas Sydenham, England’s first great physician, who lived in the 17th century and studied early history. Next came typhoid and relapsing fever, plague and other pestilential fever, smallpox and dysentery’s-the latter a generic class of disease that includes what’s known as dysentery, as well as cholera.

The ancients had no inkling as to the true cause of their misery. People believed divine retribution caused plagues and epidemics, or else bad air, or conjunction of the planets and stars, any and all of these things.

Ignorance Ain’t Bliss! How else to explain healthy people suddenly falling dead within hours and soldiers struck down with no signs of wounds? What else would cause such excruciating deaths, accompanied by delirium or hallucination, the body wracked by yellow or green or black vomit or excreta; or covered with obscene black boils, terrible red rushes or ghastly blue pallor? Why else would such sickness remain for months, then leave suddenly and not reappear till years later? Or perhaps it was replaced by a plague more deadly.

Hippocrates, the “Father of Medicine” who lived around 350 B.C., recommended boiling water to filter out impurities – those particles that pollute its sweet taste, mar its clarity or poison the palate.

He was onto something, but his advice pertained only to what the observer could taste, touch, smell or see with the naked eye. The “what you see is what you get” approach was about the extent of scientific water analysis until the late 1800s.

That invisible organisms also thrive and swim around in a watery environment was beyond imagination until a few centuries ago, and their connection with disease wasn’t established till a scant 100 years ago. Although the microscope was invented in 1674, it took 200 years more for scientists to discover its use in isolating and identifying specific microbes of particular disease. Only then could public health campaigns and sanitary engineering join forces in eradicating ancient and recurring enteric diseases, at least in developed countries of the world.

Cleaning Up: From archeology we learn that various ancient civilizations began to develop rudimentary plumbing. Evidence has turned up of a positive flushing water closet used by the fabled King Minos of Crete back around 1700 B.C. The Sea Kings of Crete were renowned for their extravagant bathrooms, running hot and cold water systems, and fountains constructed with fabulous jewels and workings of gold and silver.

Just a few months ago, a colorful public latrine dating to the 4th century B.C. was unearthed on the Aegean island of Amorgos. The 7’x 5′ structure resembles a little Greek temple. Topped with a stone roof, the interior walls decorated in red, yellow and green plaster, it served a gymnasium a short distance away. The building accommodated four people seated on two marble benches. Running water flushed the wastes away, probably along an open ditch at the users’ feet.

Ancient water supply and sewerage systems – along with various kinds of luxury plumbing for the nobility – also have been discovered m early centers of civilization such as Cartage, Athens and Jerusalem as well. But it was the Roman Empire of biblical times that reigns supreme, by historical standards, in cleanliness, sanitation and water supply.

The Romans built huge aqueducts conveying millions of gallons of water daily, magnificent public baths and remarkable sewer systems – one of which, the Cloaca Maxima, is still in use. Rome spread its plumbing technology throughout many of its far-flung territories as well.

Yet, while we may rightfully marvel at the Roman legacy in plumbing, it should be noted that they were motivated by concerns of esthetics, comfort and convenience. They understood very well that bringing fresh water to the masses and disposing of waste made for a more pleasant way of life, but there is little evidence they understood the connection with disease control.

Bursting Rome’s Bubble: In fact, the magnificence great city-state diminishes quite a bit when its plumbing systems come under closer scrutiny. Rome sprang up in haphazard fashion, a town of crooked, narrow streets and squalid houses. In its heyday, Rome had a population of over one million, and waste disposal was a definite problem.

The water supply of Rome was obtained from ground water and rain water, and in many cases these mixed together. The lowlands of the countryside were swampy marshes which developed into malarial wastelands. The Romans developed underground channels to drain the natural swamps and secure water for irrigation and drinking. Nonetheless, a particular region known as the Pontine Marshes were all but inhabitable during the summertime, until drained during the regime of Benito Mussolini. (Some 40,000 Italians died in a 16th century malaria epidemic.)

A luxury toilet in the private houses of the well-to-do was a small, oblong hole in the floor, without a seat – similar to toilets that prevail in the Far East and other sections of the world even today. A vertical drain connected the toilet to a cesspool below.

The great Roman spas accommodated hundreds and even thousands of bathers at a time. But without filtration or circulation systems, the bathers basked in germ-ridden water and the huge pools had to be emptied and refilled daily.

In public latrines, a communal bucket of salt water stood close by in which rested a long stick with a sponge tied to one end. The user would cleanse his person with the spongy end and return the stick to the water for the next one to use. The stick later evolved into the shape of a hockey stick, and the source for the expression “getting hold of the wrong end of the stick.” It also provided an excellent medium for passing along bacteria and the assorted diseases they engendered.

Running water for the latrine either was supplied by stone water tanks or else by an aqueduct patterned after the graceful, curved arches made famous by the Roman engineers. Those water experts knew that covering water keeps it cool from the sun and helps prevent the spread of algae.

Imperfect though their plumbing knowledge may have been, the Roman Empire still did an admirable job assuring public cleanliness and, inadvertently, health. Rome employed administrators known as aediles to oversee various public works, including coliseum games and the police. They also were in charge of seeing that streets got swept of garbage and streams cleared of visible pollution and debris.

in aid.

Decline & Fall: Though the Roman Empire would last until the6th century A.D., its fall was preceded by centuries of gradual decay, conflict and unrest. Ironically, some historians suggest that the Roman plumberi (plumbers) may have played a significant role in the downfall due to their extensive use of lead.

So prized was the craftsmanship of these plumberi that in lieu of present – day status symbols like a Rolls Royce or Porsche, our Roman ancestors boasted of lead pipes in their houses, especially those imprinted with the plumber’s name (usually female, by the way), and that of the building owner.

Lead poisoning is at least a plausible explanation for the dementia of Roman emperors such as Caligula and Nero, and for a general weakening and demoralization of the populace at large. However, the case for massive lead poisoning is far from proven, and water piping was hardly the only source of lead contamination. The widespread use of lead cooking utensils and goblets probably was more harmful than its use in plumbing.

Whatever the causes, over time there was a noticeable deterioration in the moral values, dignity and physical character of Roman society. Symbolic of this general decline, by the time of Augustus Caesar in 14 A.D., the once authoritative aediles collected the waste only at state-sponsored events.

During the final century of Roman domination, there was a succession of earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and disease epidemics. Soon afterwards, rampaging Vandals and other barbaric tribes completed the breakdown of Western civilization, as they systematically leveled and defiled the great Roman cities and their water systems.

Then came a thousand years of medieval squalor. A thousand years of sicknesses and plague of unbridled virulence, fanned by fleas and mosquitoes, excrement and filth, stagnant and contaminated water of every description.

Age Of Disease: The typical peasant family of the aptly-named Dark Ages lived in a one-room, dirt-floor hovel, with a hole in the thatched roof to let out the smoke of the central fire. The floor was strewn with hay or rushes, easy havens for lice and vermin. Garbage accumulated within. If they were lucky, the family had a chamber pot, though more likely they relieved themselves in the corner of the hovel or in the mire and muck outside.

Water was too precious to use for anything except drinking and cooking, so people rarely bathed. Heck, they barely changed clothes from one season to another, wearing the same set every day, perhaps piling on more rags for warmth.

These are the conditions which spawned the infamous Black Plague, killing an estimated one third of the European population. Although not directly related to bad plumbing, the plague serves as the most striking example of misery caused by poor sanitation in general, and the ignorance of people in controlling the outbreak.

The first of several waves hit England in 1348, caused by flea bites spread by lice that dwelled on host black rats. They, in turn, fed on the garbage and excrement of the masses. London became largely deserted. The King and Queen and other rich people fled to the countryside. The poor were the greatest sufferers.

Panic, death and despair followed the abandonment of farms and towns. Wrote William of Dene, a monk of Rochester in Kent, England, Men and women carried their own children on their shoulders to the church and threw them into a common pit. From these pits such an appalling stench was given off that scarcely anyone dared to walk beside the cemeteries, so marked a deficiency of labors and workmen that more than a third of the land in the whole realm was left to.”

So bad was the “Black Death,” the Great Fire of London in I 666 can be viewed as a blessing in disguise. Though it killed thousands of people, the holocaust also consumed garbage, muck and black rats, effectively ending the plague.

Camp Killers: Bad plumbing was merely one of many sanitation factors that gave rise to the Black Death. Other scourges are more directly related to human waste. Dysentery is one that has left an indelible mark on history.

Characterized by painful diarrhea, dysentery is often called an army’s “fifth column.” Identified as far back as the time of Hippocrates and before, it comes in various forms of infectious disorders and is said to have contributed to the defeat of the Crusaders. Wrote the eminent English historian, Charles Creighton: “The Crusaders of the 11th – 13th centuries were not defeated so much by the scimitars of the Saracens as by the hostile bacteria of dysentery and other epidemics. ”

The summer of the first Crusade in 1090 was extraordinarily hot as the ill-prepared and rag-tag “army” of men and camp followers went to war with little more than the clothes on their backs-confident that the Lord would provide for their needs in such a holy cause. They denuded the land of trees and bushes in the quest for nourishment. Hampered by lack of fresh water and contaminated containers, they trudged along to their destiny, relieving themselves along the wayside or in the fields.

Dysentery hit the women and children first, and then the troops. More than 100,00 died plus almost 2,500 German reinforcements whose bodies remained unburied.

Typhus fever is another disease born of bad sanitation. It has come under many headings, including “jail fever” or “ship fever,” because it is so common among men in pent-up, putrid surroundings. Transmitted by lice that dwell in human feces, the disease is highly contagious.

Napoleon lost thousands of his men to typhus in Russia – as did the Russians who caught it from the enemy. Many historians believe that Napoleon would have won were it not for the might of his opponents “General Winter, General Famine and General Typhus.”

French ships were notorious for their filthy and fever-ridden sailors. One such French squadron left its soiled clothing and blankets behind near Halifax, Nova Scotia, when they returned to Europe in 1746, thinking they could dispel their own plague. Their infected blankets wiped out a nation of Indians.

Typhoid fever, a slightly different ailment than typhus, involves a Salmonella bacillus that is found in the feces and urine of man. The symptoms are so similar to typhus that the two were not differentiated until 1837. Prince Albert died from typhoid in 1861. His wife, Queen Victoria, had built-in in-immunity because of a previous siege. Good thing, because she is said to have prostrated herself in grief across the dead body of her beloved husband.

Ten years later, Victoria’s son, Edward, almost died from the disease. A plumber traced the contamination to the lines of a newly-installed water closet and fixed the problem. Edward, the Prince of Wales, was very grateful to the plumber. Word spread of this episode and is thought to have hastened the acceptance of the indoor water closet in England.

By the time of the Boer War in 1899-1901, anti-typhoid inoculation was available. By then, typhoid fever was recognized as a waterborne disease, and that the germ could be killed by filtering and boiling water. Far from home in South Africa, the undisciplined British troops succumbed to the hot climate and drank straight from the rivers. Of 400,000 troops, 43,000 contracted typhoid.

Closer to home, typhoid raged on in colonial New York and Massachusetts. It reappeared for the last time in epidemic form in America in the early 1900s, compliments of the celebrated Typhoid Mary.

Mary Maflon was a cook for the moneyed set of New York State; her specialty was homemade ice cream. Officially, she infected 53 people – with three deaths – before she was tracked down. Unofficially, she is blamed for some 1,400 cases that occurred in 1903 in Ithaca, where she worked for several families. Never sick herself, it took a lot of persuasion by authorities to convince her that she was a carrier of the disease. Health authorities quarantined her once, let her go, then quarantined her for the rest of her life when another outbreak occurred.

The Cholera Story: The bad news is that another waterborne disease, cholera, has proven one of history’s most virulent killers. The good news is that it was through cholera epidemics that epidemiologists finally discovered the link between sanitation and public health, which provided the impetus for modem water and sewage systems.

With 20th – century smugness, we know cholera is caused by ingesting water, food or any other material contaminated by the feces of a cholera victim. Casual contact with a contaminated chamber pot, soiled clothing or bedding, etc., might be all that’s required.

The disease is stunning in its rapidity. The onset of extreme diarrhea, sharp muscular cramps, vomiting and fever, and then death – all can transpire within 12-48 hours.

In the 19th century cholera became the world’s first truly global disease in a series of epidemics that proved to be a watershed for the history of plumbing. Festering along the Ganges River in India for centuries, the disease broke out in Calcutta in 1817 with grand – scale results.

India’s traditional, great Kumbh festival at Hardwar in the Upper Ganges triggered the outbreak. The festival lasts three months, drawing pilgrims from all over the country. Those from the Lower Bengal brought the disease with them as they shared the polluted water of the Ganges and the open, crowded camps on its banks.

When the festival was over, they carried cholera back to their homes in other parts of India. There is no reliable evidence of how many Indians perished during that epidemic, but the British army counted 10,000 fatalities among its imperial troops. Based on those numbers,, it’s almost certain that at least hundreds of thousands of natives must have fallen victim across that vast land.

When the festival ended, cholera raged along the trade routes to Iran, Baku and Astrakhan and up the Volga into Russia, where merchants gathered for the great autumn fair in Nijni-Novgorod. When the merchants went back to their homes in inner Russia and Europe, the disease went along with them.

Cholera sailed from port to port, the germ making headway in contaminated kegs of water or in the excrement of infected victims, and transmitted by travelers. The world was getting smaller thanks to steam-powered trains and ships, but living conditions were slow to improve. By 1827 cholera had become the most feared disease of the century.

The Laughter Died: It struck so suddenly a man could be in good health at daybreak and he buried at nightfall. A New Yorker in 1832 described himself pitching forward in the street “as if knocked down with an ax. I had no premonition at all.”

The ailment seemed capable of penetrating any quarantine of harbor or city. It chose its victims erratically, with terrifying suddenness, and with gross and grotesque results.

Acute dehydration turns victims into wizened caricatures their former selves. The skin becomes black and blue, the hands and feet drawn and puckered. The German poet Heinrich Heine described an outbreak in Paris in a letter to a friend: “A masked ball in progress … suddenly the gayest of the harlequins collapsed, cold in the limbs, and underneath his mask, violet blue in the face. Laughter died out, dancing ceased and in a short while carriage-loads of people hurried from the Hotel Dieu to die, and to prevent a panic among the patients were thrust into rude graves in their dominoes [long, hooded capes worn with a half-mask). Soon the public halls were filled with dead bodies, sewed in sacks for want of coffins … long lines of hearses stood in queue…”

The worldwide cholera epidemic was aided by the Industrial Revolution and the accompanying growth of urban tenements and slums. There was little or no provision at all for cesspools or fresh water supplies. Tenements rose several stories high, but cesspools were only on the ground floor with no clear access to sewers or indoor running water. It didn’t make much difference, because until the 1840s a sewer was simply an elongated cesspool with an overflow at one end. “Night men” had to climb into the morass and shovel the filth and mire out by hand. In most cases, barrels filled with excrement were discharged outside, or contents of chamber pots flung from open windows – if there were any – to the streets below.

Water hydrants or street pumps provided the only source of water, but they opened infrequently and not always as scheduled. They ran only a few minutes a day in some of the poor districts. A near riot ensued in Westminster one Sunday when a water pipe that supplied 16 packed houses was turned on for only five minutes that week.

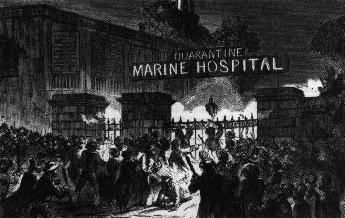

Cholera first hit England through the town of Sunderland, on October 26, 1831. One William Sproat died that day from the disease, though nobody wanted to admit it. Merchants and officials found plenty of reasons to rationalize away a prospective 40 day maritime quarantine of the ports.

England was reaping the profits of the Industrial Revolution. and a quarantine of ships would be catastrophic for the textile industry. At any rate, the medical profession held that cholera wasn’t contagious. Public health administration was in its infancy, and so disorganized that the leading doctor didn’t know there were two infected houses only a short distance away from each other. He learned of the “coincidence” three months later.

The American Experience: American hygiene and sanitation were not much better. Cholera spread through immigrants from the infected countries, Ireland in particular, whose masses were fleeing the poverty and despair of the potato famine. Those who could scrape together three pounds for passage left for North America.

Life aboard an immigrant ship was appalling as ship owners crowded 500 passengers in space intended for 150. Infected passengers shared slop buckets and rancid water.

The contagion spread as soon as the immigrants landed. In one month, 1,220 new arrivals were dead in Montreal. Another 2,200 died in Quebec over the summer of 1832.

Detroit became another focal point of cholera. Instead of drawing fresh water from the Detroit River, people used well water. The land was low and it was much more convenient. But outhouses placed at odd locations soon contaminated those wells, and cholera spread quickly.

Cholera entered New York through infected ships. City people started clogging the roads in an exit to the countryside. On June 29, 1832, the governor ordered a day of fasting and prayers – the traditional response by government to treating the disease. After July 4, there was a daily cholera report.

Quarantine regulations which sought to contain towns and cities in upper New York, Vermont and along the Erie Canal met with little success. Immigrants leaped from halted canal boats and passed through locks on foot, despite the efforts by contingents of armed militia to stop them.

Some doctors flatly declared that cholera was indeed epidemic in New York, but more people sided with banker John Pintard that this “officious report” was an “impertinent interference” with the Board of Health. The banker incredulously asked if the physicians had any idea what such an announcement would do to the city’s business.

Visitors were struck by the silence of New York’s streets, with their unaccustomed cleanliness and strewn with chloride of lime (the usual remedy for foul-smelling garbage). Even on Broadway, passersby were so few that a man on horseback was a curiosity. One young woman recalled seeing tufts of grass growing in the little-used thoroughfares.

Big news was unfolding in England then, but no one realized the significance.

Steadfast Ignorance: The eminent Dr. John Snow demonstrated how cases of cholera that broke out in a district of central London could all be traced to a single source of contaminated drinking water. Sixteen years later Snow would win a 30,000 franc prize by the Institute of France for his theory that cholera was waterborne and taken into the system by mouth.

But Snow’s original work received little attention from the medical profession. He was attacked at the weakest point – that he could not identify the nature of the “poison” in the water.

By the end of the first cholera epidemic, the relationship between disease and dirty, ill – drained parts of town was rather well established. This should have spurred sanitary reform. But little action followed.

An out-of-sight, out-of-mind syndrome developed when the first epidemic ended. The learned Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal at one point declared they would review no more books on the subject “because of the multitude of books which have recently issued from the press on the subject of cholera, and our determination to no longer try the patience of our readers.”

When the second cholera epidemic hit England in 1854, Snow described it as “the most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in this kingdom.” At least it provided him with an opportunity to test his theory.

By charting the incidence of the disease, he showed that over 500 cases occurred within 10 days over a radius of some 250 yards centered on London’s Broad Street. He looked for some poison which he believed came from the excreta of cholera patients and swallowed by the new victims. A common factor was their use of water that had been polluted with sewage. Snow had traced the pipelines of various water companies and showed that one was infected by cholera.

By the methodical process of elimination, he proved his point: A workhouse in that area had its own private well, and there were only 5 deaths among its 535 inmates. A brewery on Broad Street likewise never used the water from the Broad Street pump, and it had no cases among its 70 workers.

The actual discovery of the comma-shaped bacillus of cholera was made by the German Dr. Robert Koch in 1876. Through microscopic examination, he ascertained that excrement may contain cholera bacteria a good while after the actual attack of the disease.”

Final Obstacles: Cholera was always the worst where poor drainage and human contact came together. This of course was apt to be in crowded slums.

So at first, those on top of the social heap could reassure themselves that pestilence attacked only the filthy, the hungry and the ignorant. When the cholera epidemic first hit Paris, there were so few deaths outside of the lower classes, that the poor regarded the cholera epidemic as a poison plot hatched by the aristocracy and executed by the doctors. In Milwaukee, efforts to apply basic health measures were thwarted by rag-pickers and “swill children” who saw the removal of offal and garbage from the streets as a threat to their livelihood. As one newspaper editorialized, “It is a great pity if our stomachs must suffer to save the noses of the rich.”

The immunity enjoyed by the wealthy was short-lived, however. The open sewers of the poor sections eventually leached into the ground and seeped into wells, or ran along channels into the rivers that supplied drinking water for whole towns and cities. Once the rich and the movers and shakers of society began to get sick, government reform began.

Thus it happened that most municipal water mains and sewer systems got built in the late 19th century in America. Public health agencies got formed and funded. Building codes and ordinances got passed and enforced.

The superstitions of the ages had finally run their course. Mankind began to understand that the evil spirits causing its woes were microscopic creatures that could be defeated by plumbers and sanitary engineers.

Plumbers finally got to show their stuff in a way that had not been seen since the days of the Roman Empire.