courtesy of The Seattle Times, 10/8/97

by FRANK GREVE / Knight-Ridder Newspapers

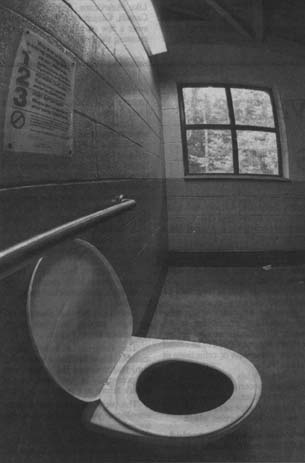

DELAWARE WATER GAP, Pa. – There’s a remarkable new building in a federal park in Pennsylvania: a two-hole outhouse, without running water, that cost the National Park Service at least $333,000.

It’s nestled amid evergreens, with a gabled slate roof, cottage-style porches, and a handsomely tapered cobblestone masonry foundation in the manner of Frank Lloyd Wright. A medley of wildflowers hides any sign of new construction.

Inside each spacious restroom, a green horizontal stripe at baseboard level plays off the green of hemlocks visible through discreetly placed picture windows. The place smells as sweet as the woods.

Clearly, this is an outhouse worthy of Better Homes and Gardens magazine. And it should be. More than a dozen Park Service designers, architects and engineers had a hand in it by the time the privy opened in May 1996. They took two years.

The product, while magnificent, is typically expensive for Park Service work. How typical? So typical Park Service officials don’t consider this six-figure privy expensive.

“We could have built it cheaper, yes, but we wanted someone coming up the trail or off the road to encounter a nice restroom facility,” says Roger Rector, the park superintendent who signed off on the new outhouse in 1995.

“Frankly, that’s what we’re paying for toilets,” shrugs Dennis Galvin, deputy director of the National Park Service. They’re meant to last 50 years or longer with little maintenance, he explains, and top-quality construction naturally costs more. Lots more.

The hemlock-matching paint designers specified, for example, is custom-mixed epoxy resin that costs $78 a gallon. Certified Joe Pye Weed seed called for in its wildflower design cost $720 a pound. The toilets are no mere holes in the ground; they’re $13,000 state-of-the-art composting models custom built by Advanced Composting Systems of Whitefish, Mont.

Capstones that serve as porch railings are of quarried Indiana limestone. The clapboard siding is one-inch cedar. And, while local slate has been good enough for Pennsylvania homes for centuries, it wasn’t good enough for this outhouse. So slate was shipped in from Vermont.

Earthquake safe

If there’s an earthquake, don’t worry. This may be the only privy in Pennsylvania with a 29-inch-thick foundation designed to withstand one. But don’t show up in midwinter. The doors will be locked because composting toilets don’t work in freezing temperatures. Don’t ask for water either. There isn’t any.

“It’s beautiful, but I’m glad I always travel with Handi Wipes,” remarked Ann Jones of Woodbridge, N.J., after a brief stop at the comfort station. “At first,” she added, “I thought it was a visitor center.”

In a two-hour time span on a sunny Saturday in September, Jones was one of 10 visitors to the facility, located at a trailhead in a lovely, remote ravine 300 yards from Raymondskill Falls in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Summer traffic is heavier, according to park personnel, but on weekdays in fall the 20-car parking lot often is empty.

Just how the outhouse in Pennsylvania came to be built – came, in fact, to rank 10th nationwide among the National Park Service’s 1994 construction priorities – is the story of a government construction program that has had three big problems:

Politicians set most of the Park Service’s construction priorities. Park Service architects designed their dreams. No one questioned costs.

Special park designers

That’s not so surprising. Lawmakers don’t mind Washington’s splurging in their districts. Park superintendents need lawmakers’ favor. And Park Service designers and architects have no reason to curb costs. Quite the opposite. They work out of a centralized office, the Denver Service Center, that depends for its revenues, not on congressional appropriations, but on commissions that are a percentage of the cost of the projects they design.

“They’re a bunch of prima donnas who just want to win awards for design excellence,” grouses Jack Wilburn, recently retired chief of maintenance at the Gulf Islands National Seashore on the Florida and Mississippi coast. “Cost doesn’t bother them; they always want to do something monumental and unique.”

By way of cost comparison to the Raymondskill outhouse, Wilburn says he designed and built permanent comfort stations on environmentally sensitive islands for about $20,000. At the Delaware Water Gap park, portable toilets in widespread use cost $500 a unit. The Park Service doesn’t buy them, however; they’re leased and serviced for $65 a month from Pocono Potties in Snydersville, Pa. (Motto: “We’ll care.”)

Three paths for money

To build the Raymondskill outhouse, the Park Service spent money in three different ways: planning and design, construction, and supervision of the contractor. For planning and design, the bill was $102,614. For supervision – by a Park Service engineer from Denver who lived on site in Pennsylvania for 10 months – the bill was $81,220.

The Park Service and the outhouse builder disagree over actual construction costs. The contractor, James Straka of Peckville, Pa., low bidder among six, says building the outhouse cost him $262,000. But the Park Service’s Denver-based manager of the job, Michael Giller, estimates it cost “$150,000 to $200,000.”

If Giller’s right, the total was between $333,000 and $383,000. If the contractor is right, it cost more than $445,000. That doesn’t include costs of the parking lot, new signs, an improved trail to the waterfall and other outlays.

Maintenance backlog

You could say this is no big deal. National park construction is certifiably gorgeous; it’s won more presidential design awards than any other federal agency. And it’s not that much money in terms of the federal budget: the Park Service’s $1.99 billion construction budget for the last 10 years is less than the price of a single B-2 bomber.

But one consequence of the Park Service’s penchant for custom-designed outhouses – and gates, fences and even benches – is a backlog in maintenance and construction work that’s grown in the 1990s from $2 billion to nearly $5 billion, according to Park Service testimony before Congress.

Some parks in the districts of powerful lawmakers are flush – Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area near Cleveland, for example, in the district of Interior Appropriations Subcommittee Chairman Ralph Regula, R-Ohio – but hundreds of parks without allies in Congress are deteriorating badly.

Congressional roll

Rep. Joseph McDade, the No. 2 Republican on the powerful House Appropriations Committee, is the patron of the Pennsylvania privy. The Delaware Water Gap park lies within McDade’s district and he insisted on its high priority. Still does, in fact. The 1998 budget includes $4.1 million for trail improvements there.

McDade, shown photos of the outhouse by a reporter, initially thought it was a restored resort cottage. “That’s terrible,” he said, once convinced it was an outhouse. “It’s a Taj Mahal! Why the hell did they do that?” The lawmaker said he never realized an outhouse was part of the appropriations package he pushed entitled “Raymondskill Falls Improvements.”

“All I do is send them the money,” McDade continued. “I don’t try and micromanage the park.”

Political sponsorship like McDade’s is essential these days when it comes to Park Service construction. Of the 75 projects Congress has agreed to pay for in 1998, the Park Service selected only 25. The other 50, according to the Park Service’s Galvin, were “congressionally identified.” That’s a euphemism for pork-barrel spending. In effect, Congress agreed to $60 million in construction that the Park Service asked for, then added about $90 million for projects lawmakers were pushing.

No standardized privy

Since lawmakers, in effect, set most of the Park Service’s priorities and decide how much to pay for them, Service Center architects are free to concentrate on the challenge that’s their greatest perk: doing great design work on sites of great natural beauty.

In the case of comfort stations, a standardized design might make them cheaper, but that’s not the way Park Service designers think. Standardization is “sort of a Sixties concept,” explained Tom Solon, the recreation area’s chief architect: “It has some merit for the military or McDonald’s,” he explained, “but each national park has unique needs.”

He believes fervently that the Park Service’s mission includes design and construction work superior to most commercial work. “We’re going to be criticized for high costs,” Solon observed, “but we have to set a good example.”

Solon’s attitude is his bosses’. In fact, all of the “dozens” of comfort stations the Denver Service Center has produced in recent years were custom-designed and custom-built, according to Center director Charles Clapper.

That includes the latest, a six-hole facility at the Thomas Stone National Historic Site in Port Tobacco, Md. It’s a tiny park on a Potomac River cove south of Washington. Its namesake signed the Declaration of Independence and its champion is House Appropriations Committee member Steny Hoyer, D-Md.

“We figure that if we have a comfort station, we can invite bus groups,” explains a hopeful park official at Thomas Stone, which, at the moment, has only one bathroom. The winning construction bid was $420,000 for a facility that, in order to blend in with nearby subsistence farms, will look like a corn crib.

Some explanations

There are explanations for some high costs. The outhouse paint at Raymondskill Falls, for example, is said to have remarkable durability. The weed seed used there – of which less than a pound was bought – was needed to restore the natural environment. The composting toilets solved water-quality problems. Slate roofs last 75 years.

An on-site construction supervisor from Denver was needed, according to resident architect Solon, because Solon was too busy on other projects. Besides, that’s standard practice on projects that Denver designs. For the same reasons, a landscape architect from Denver was used instead of the park’s local one.

There’s an odd circumstance behind the $102,614 in design costs: Two-thirds of the money went for construction documents. Partly, that’s because Park Service architects specify everything, right down to the size of the hole for the lock in the parking lot gate.

In addition, all Park Service measurements for the Raymondskill outhouse were metric. That was to oblige a federal mandate to promote the metric system. After two such projects, Clapper recalled, Denver concluded that metric planning documents discouraged potential bidders and went back to feet and inches.

Contractor Straka, who says he lost money on the job, had no problem with metric specifications, he said in a telephone interview. The problem was specifications so tight, he continued, and the on-site inspector so insistent on them, that “I wanted to pin him to a tree with a pick.”

His adversary, inspector Stephen Herzog, acknowledges the tension. “We were like brothers,” he recalled in a telephone interview from his new assignment at the Grand Canyon. “One minute we were at each other’s throat; next minute, we were pulling together hard as we could to build that sucker.”

Not at ‘minimum cost’

To lawmakers, the painstaking perfectionism and high cost of Park Service construction come as no surprise. The same 1994 Interior Appropriations conference report that paid for the Pennsylvania privy cautioned that “The Park Service must begin looking at construction projects as we would our own budgets, i.e., is there a lower cost alternative?”

Two years later, investigators for the General Accounting Office, Congress’ watchdog arm, wrote that Park Service construction projects were “plagued by nagging suspicions that design solutions are not achieved at minimum cost.”

To meet the criticism, the Denver Service Center appointed project managers to monitor costs. They’re subordinate to park superintendents, however. Moreover, under the current system, superintendents don’t get to keep for their parks the money they might save.

Instead, “Superintendents know money is scarce,” according to a senior Interior Department official in Washington familiar with Park Service construction, “so you go for all you can get. You figure ‘Now’s my chance; I’ve gotta get all I can when the brass ring comes around.’ ”

So, to the extent Congress has pressed for reform, it’s pressed Park Service headquarters in Washington to change its construction policies.

Typically that job has fallen to Deborah Weatherly, the House Interior Appropriations subcommittee’s top staffer. When the Raymondskill Falls appropriation went through, her boss was Rep. McDade.

Copyright © 1997 The Seattle Times Company, 10/8/97